Ayshah Fazeenah AH1*, 2Fasmiya MJA, Sithy Fowziya AW1, Mohammed Aleemuddin Quamri3

1Department of Moalejat, Institute of Indigenous Medicine, University of Colombo, Rajagiriya, Sri Lanka.

2Bandaranayake Memorial Research Institute, Navinna, Sri Lanka.

3Department of Moalejat, National Institute of Unani Medicine, Kottigepalya, Bangalore-560091, India.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Volume 3, Issue 2, Page 102-105, May-August 2015.

Article history

Received: 23 July 2015

Revised: 27 July 2015

Accepted: 29 July 2015

Early view: 21 August 2015

*Author for correspondence

E-mail: [email protected]

Background: Migraine is the second most common primary headache disorder and is the nineteenth most common cause of disability worldwide. One of the ancient medical techniques mentioned in the Unani system of medicine is wet cupping to reduce the use of analgesics in migraine. It is a simple, effective and cost-effective treatment in several diseases. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of wet cupping in the management of migraine.

Materials and methods: A Randomized single blinded clinical study was conducted from March 2014 to November 2014 in the outpatient department of Base Ayurveda Hospital, Kappalthurai, Trincomale. 40 patients, aged 20-60 years were selected. Wet cups were applied on 0th day, 15th day and 30th day. The effectiveness of the study was assessed by using Visual Analog Score (VAS) in 3 follow ups. Data were analyzed by repeated measure of ANOVA with paired t-tests.

Results: Results suggested that, compared to the baseline, the means for pain intensity at the beginning and the end of the study were significantly decreased (p<0.01). In most patients pain was intolerable before therapy; however, after the first and second sessions of therapy, pain lessened was significant.

Conclusion: This study revealed that the wet-cupping leads to clinical relevant benefits for migraine.

INTRODUCTION

Migraine is defined by the International Headache Society (IHS) as a recurrent headache that occurs with or without aura and lasts 2–48 hours (Anonymous, 2004). It is a common episodic neurological condition, (Sid Gilman, 2010) associated with certain features such as sensitivity to light, sound, or movement; nausea, vomiting (Fauci et al., 2008), photophobia, and phonophobia are common accompanying symptoms with headache (Anonymous, 2004). Migraine pain is characterized by an intense and throbbing unilateral in nature, (Carlos et al., 2003) pulsating in quality, of moderate or severe intensity, and is aggravated by routine physical activity (Anonymous, 2004). It is the second most common primary headache disorder, (Goldman, 2007) of the brain produced by dysfunctional brainstem regulation of cranio-vascular afferents (Sid Gilman, 2010). This is the nineteenth most common cause of disability worldwide, which reduces the social life of people who suffer from it by about 60% and may become a lifelong disability (Anonymous, 2015). It occurs in up to 11% of the adult population, usually with onset in late adolescence or the early third decade (Sid Gilman, 2010). According to the World Health Organization, it affects two thirds of men and 80% of women in developed countries (Anonymous, 2015).

Shaqeeqah is an Arabic word which is derived from the word “Shaq” which means a part or a side, due to which it is named as Shaqeeqah (Tabri, 1995). The cause of migraine is either riyah haar (hot air) or imtila (congestion) (Zohar, 1986). Galen has defined this pain as it examines the weakness of one side of head and reaches to the centre of the head and the weaker side accepts this pain (Kabeeruddin, 2009). According to Ibn Sina (Avicenna), the causes of migraine are located inside the cranium. Sometime it is in the membrane of cranium, but often in the muscles of temporal area. The morbid matter responsible for migraine can develop locally at the site of pain or in external arteries, inside the brain or in the brain membrane. Many times migraine can be because of bukharat (vapour) ascendeds from whole body but often it is due to morbid akhlat (humors), which can be hot, cold, riyah (air), bukharat (Ferri et al., 2008).

Wet cupping is one of the ancient medical techniques mentioned in the Unani system of medicine to reduce the use of analgesics in migraine. Cupping therapy is a simple, effective and cost-effective treatment in several diseases. Ancient Egyptians were reported to practice cupping therapy earlier than many old civilizations, where cupping therapy was one of the oldest known medical therapies in ancient Egypt. The first report of using cupping therapy in ancient Egypt dates back to 1550 B.C. (more than 3500 years ago) where drawings on the famous Egyptian papyrus paper and ancient Egyptian temples showed that Egyptians were advanced in treatment using cupping therapy. Cupping therapy was also used in ancient Greek medicine (Sayed et al., 2013).

There are mainly two techniques of cupping therapy are used today, dry cupping and wet cupping. Cupping therapy is a simple procedure in which negative pressure is applied to the skin through sucking cups (dry cupping therapy) (Al Shama et al., 2009). Dry cupping simply pulls the local underlying tissue up into the suctioning cup. Wet cupping therapy (Al-hijamah bil shrut) is an excretory form of therapy in which uses negative pressure suctioning and skin pricking to open the skin barrier and excrete a bloody mixture of fluids with soluble wastes and causative pathological substances (CPS) (Sayed et al., 2013). Our work focused on wet cupping, and its utility in treating chronic tension and migraine headache disorders. Headache is one of the most prevalent human disorders worldwide; with recent estimates suggesting up to 46% of the world population suffers from an active headache disorder (Alireza et al., 2008).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted from March 2014 to November 2014 in the outpatient department of Base Ayurveda Hospital, Kappalthurai, Trincomale, Sri Lanka. 40 diagnosed patients of migraine from both genders between 20-60 years of age and who willing to follow the informed consent and comply with the study procedures were selected according to Diagnostic criteria for migraine (Warrell et al., 2003), (after Goadsby and Olesen (1996) and adapted from the International Headache Society (Table-01)). Pregnant and lactating mothers, severe cardiovascular diseases and hypothyroidism were excluded from the study. Concomitant treatment was not allowed during treatment, the patients who were taking any other medicine as a treatment of migraine were advised to abstinence for a week from consuming those drugs before commencing the treatment. Participants were advised to strictly avoid foods which may aggravate migraine usually.

Patients were prescribed a series of 3 staged wet-cupping treatments, placed at 2 weeks intervals as on 0th day, 15th day and 30th day. The changes in the intensity of severity of headache, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia and impaired physical activity were considered at the baseline and also after 30 days of treatment. The effectiveness of the study was assessed by using 5 point Visual Analog Score (VAS) in 3 follow ups.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of wet cupping therapy in the management of migraine.

Wet-cupping was performed using vacuum cups with plastic vessels. The recommended site for wet-cupping in chronic headache is between the two scapulas, opposite the T1–T3 scapular spine. Each wet-cupping treatment procedure took about 20 min and was conducted in 5 phases:

1. Primary sucking. The cup is placed on the selected site and the cupper rarefies the air inside the cup by electrical or manual suction. The cup clings to the skin and is left for a period of 3 to 5 minutes.

2. Scarification. Superficial incisions are made on the skin using 15–22 gauge surgical blades.

3. Bloodletting. The cup is placed back on the skin, using the same manner described above, until it is filled with blood from the capillary vessels.

4. Removal. The cup is removed, and the process is repeated 3 times.

5. Dressing.

|

Table 1. Table 1. Diagnostic criteria for migraine. Click here to view full image |

Study design: Randomized single blinded pilot study.

Statistical analysis: The changes in the intensity of severity of headache, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia and impaired physical activity in terms of Mean ± SEM were analyzed by using repeated measure of ANOVA with paired-t tests.

RESULTS

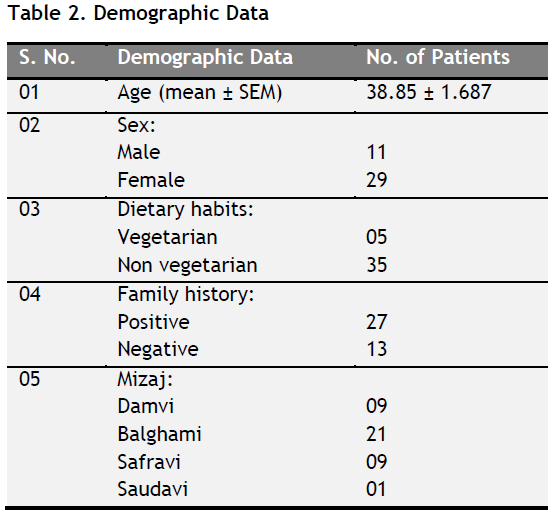

Forty patients of moderate to severe migraine between 20-60 years age, with history of headache, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia and impaired physical activity for more than 1 year of illness were treated with application of wet cupping therapy. The demographic characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 2.

|

Table 2. Demographic data. Click here to view full image |

Subjective parameters were measured on day 0, 15 and 30 (Table-3). At the end of 30th day it was found that changes in headache, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia and impaired physical activity associated with migraine were significantly reduced (p<0.01).

|

Table 3. VAS based effect of the study on subjective parameters in migraine. Click here to view full image |

The effect of 30 days treatment on headache, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia and impaired physical activity showed significant reduction with p value of <0.01 (Tables 2). There were commendable decline in mean VAS scores in headache 3.67 to 0.42 (p<0.01), nausea 2.55 to 0.20 (p<0.01), vomiting 1.10 to0.00 (p<0.01), photophobia 1.97 to 0.10 (p<0.01), phonophobia 2.05 to 0.15 (p<0.01) and impaired physical activity 2.37 to 0.07 (p<0.01).

|

Table 4. Overall effect of wet cupping therapy in migraine. Click here to view full image |

The overall effect of wet cupping therapy was determined based on the Total Symptoms Severity Score (TSSS) of mean ± SEM and Median range of subjective parameters. The TSSS before the treatment was 13.67± 0.78 and 1.15 ± 0.37 and 12.5 (24, 4) and 0(10, 0) respectively (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Forty patients were subjected for the study with age between 20 to 60 years with a mean age of 38.85 years. The 60 years old was the highest age and the 21 was the lowest age. 45% of patients were in between the age group of 31-40 and 12.5% of patients were in between 51-60 years. 72.5% were females and 27.5% were males. 67.5% of patients have a family history of migraine. These observations correspond with Sid Gilman’s (Sid Gilman, 2010) as there is a tendency for migraine to become less severe or even remit in the fifth and sixth decades, 70% of migraine sufferers are females and the risk of a child developing migraine is about 70% if both parents are affected and 45% when one parent is affected respectively.

Headache disorders are reported widely in all cultures, and the combination of migraine and tension-type headache accounts for substantial health, economic, and social costs (Lipton et al., 2003, Alireza et al., 2008). In fact, recent reports suggest headache is among the 10 most disabling conditions overall, and among the 5 most disabling for women (Stovner et al., 2007). Therefore, experimental support for underutilized treatments might be of great importance.

Following a 30-day course of 3 wet-cupping treatments, we found improvements among almost all patients in mean headache severity by alleviation of nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia and impaired physical activity.

According to Sayed et al (2013), wet cupping therapy is as an artificial surgical excretory procedure that clears blood and interstitial fluids from CPS (causative pathological substances). It opens skin barrier, enhances natural excretory functions of the skin, enhances immunity and increases filtration at both capillary ends to clear blood from CPS to restore physiology and homeostasis. Moreover, it was reported that compression pressure exerted on the skin for more than few seconds may benefit patients through the occurrence of reactive hyperemia phenomenon. In this phenomenon, vascular compression causes a decrease in blood supply to the skin for few minutes resulting in accumulation of vasodilator chemicals. Second negative pressure suctioning completes the process of waste excretion.

Building off our own experience and the writings of others (Rozegari, 2000), it seems plausible that the mechanism of wet-cupping is dominated by influences in neural, hematological, and immune system functioning. In the neural system, the main effect is likely regulation of neurotransmitters and hormones such as serotonin (of platelet), dopamine, endorphin, CGRP (Calcitoni-Gene Related Peptide) and acetylcholine. Moreover, it seems that wet-cupping has an effect on the negative charge of neuronal cells. In the hematological system, the main effect is likely via 2 pathways: (a) regulate coagulation and anti-coagulation systems, and (b) decrease the HCT (Hematocrit) and then increase the flow of blood which increase the end organ oxygenation. In the immune system, the main effect is likely via 3 pathways: (a) Irritation of the immune system by making an artificial local inflammation and then activate the complementary system and increase the level of immune products such as interferon and TNF (Tumor Necrotizing Factor); (b) effect the thymus; and (c) control traffic of lymph and increase the flow of lymph in lymph vessels (Rozegari, 2000).

CONCLUSION

A 30 day’s therapy with wet cupping application over the interscapular regions among the migraine patients was proved to be markedly effective as it resulted in alleviation of headache, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia and impaired physical activity by it clears blood and interstitial fluids from causative pathological substances from the body without any adverse effects. Therefore, we conclude that wet-cupping leads to clinical relevant benefits for migraine. Yet further studies on larger number of patients are suggested by this pilot study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Authors are highly thankful to the management of Base Ayurveda Hospital, Kappalthurai, Trincomale for their support in conducting this pilot study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

AL- Shamma YM, Abdil Razzaq A. Al-Hijamah Cupping Therapy. Kufa Medical Journal. 2009;12(1):49-56.

Alireza Ahmadi, David C. Schwebel and Mansour Rezaei. The Efficacy of Wet-Cupping in the Treatment of Tension and Migraine Headache, The American Journal of Chinese Medicine.2008;36(1):37–44.

Anonymous. BMJ Clinical Evidence and Clinical Evidence Concise EBM. 2004: 453.

http://www.federaljack.com/ebooks/BMJ. (Accessed on 21.03.2015).

Anonymous. Cupping Therapy is effective for headaches. http://www.naturalnews.com. (Accessed on 21.03.2015).

Carlos M. Villalón, David Centurión, Luis Felipe Valdivia, Peter de Vries, Pramod R. Saxena. Migraine: Pathophysiology, Pharmacology, Treatment and Future Trends. Current Vascular Pharmacology. 2003;1: 71-84.

Fauci, Braunwald, Kasper, Hauser, Longo, Jameson and Loscalzo. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 2008. 17th edition. Chapter 15- Headache. McGraw-Hill Professional, USA.

Ferri FF, Alvero R, Borkan JM, Fort GG, Dobbs MR, Goldberg RJ. Ferri‟s Clinical Advisor. 10th edition. USA: Elsevier; 2008: 13-15.

Goldman: Cecil Medicine. 2007. 23rd edition. Chapter 421 – HEADACHES AND OTHER HEAD PAIN.

Kabeeruddin. Sharah Asbab (Tarjumae Kabir Mukammal). New Delhi: Idara Kitabus Shifa. 2009:39-44.

Lipton RB, Scher AI, Steiner TJ, Bigal ME, Kolodner K, Liberman JN. Patterns of health care utilization for migraine in England and in the United States. Neurology. 60: 441–448, 2003.

Rozegari AA. The Acquaintance of Hejamat (in Farsi). Naslenikan Publishing Co, Tehran, Iran, 2000: 28–32.

Sayed SM, Mahmoud HS and Nabo MMH. Methods of Wet Cupping Therapy (Al-Hijamah): In Light of Modern Medicine and Prophetic Medicine. Alternative and Integrative Medicine. 2013;2:3.

Sid Gilman. Oxford American Handbook of Neurology. 2010.

Stovner LJ, Hagen K, R Jensen, Katsarava Z, Lipton R, Scher A, Steiner T, Zwart JA. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007:27:193–210.

Tabri M. Moalajat Buqratiya (Urdu translation). Vol. 1, New Delhi: CCRUM.1995:284-290.

Warrell, David A, Cox, Timothy, Firth, John D, Benz, Edward J. Oxford Textbook of Medicine, 4th edition, 2003:.

Zohar AMI. Kitab al Taisir (Urdu translation). 1st edition, New Delhi: CCRUM. 1986: 77-78.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.